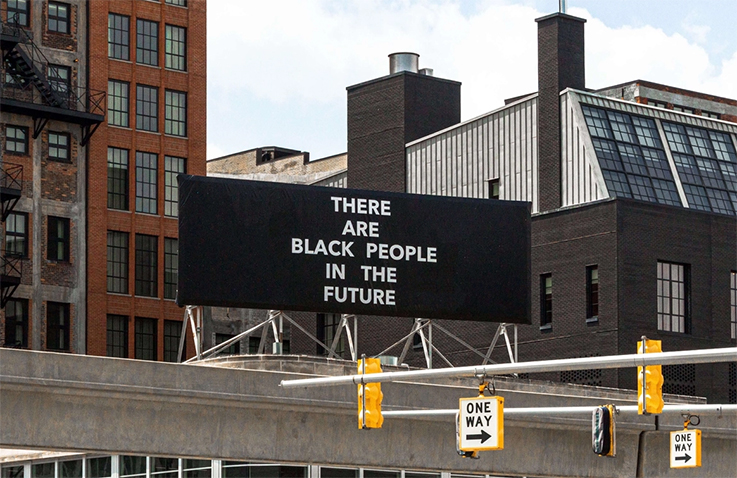

In 2012, the visual artist Alisha B. Wormsley embarked on a multiyear project in Homewood, one of Pittsburgh’s historically Black neighborhoods. Profoundly impacted by the teachings of Afrofuturism and the belief that Black people are the authors of their tomorrows, she began collecting objects from town residents. Of those she gathered, she imprinted on them an emphatic declaration: “There Are Black People In the Future.” Years later, in 2014, I came across one of Wormsley’s “artifacts” on Tumblr; it was a window pane with the statement in thick lettering, its edges rusted and chipped. At first glance, the statement seemed to be fading away. In truth, the opposite was happening—the words were coming into view. The feeling of seeing Wormsley’s artwork for the first time was immediate: I simultaneously felt transported, empowered, and proud.

Atlanta, the FX dark comedy created by and starring Donald Glover, has given me that same feeling since its debut in 2016. Alas, it’s time to bid it farewell. The show will culminate with its fourth season—it kicked off Thursday with a two-episode premiere—and bring to a close an era in television that embraced Black futurity head on.

In its final season, the outlines of the show remain as they ever were: thrillingly intangible. The brilliance of the series was always about the unsaid and the unseen (sometimes quite literally; remember the invisible car that charged through a club parking lot in season one?). To its benefit, Atlanta learned to speak between the lines. It was all in the knowing, in what didn’t need to be voiced or explained in great detail—because what was understood was already understood. At its most transcendent, Atlanta was a head nod. If you got it, you got it. Nothing else needed to be said.

Which is maybe kind of ironic when you think about it. The show has never lacked for voice—although sometimes it struggled narratively from an excess of voices; season three was congested with thematic issues—it has only asked that we listen with open ears.

Afrofuturism insists that Black people are the makers of their destiny. Atlanta’s central quartet attempted, sometimes to hilarious effect, to steer their lives on their terms. As characters they were a striking study in motion. In its four seasons, not once did they stop running to or away from the eeriness of the world, its darkness and wonder, and all the questions within.

Paper Boi (Brian Tyree Henry) best exemplified this distinct kineticism. He was both the show’s north star and, as Doreen St. Felix observed, also its “Odysseus figure.” A local rapper who finds fame, his story was as colored by the volatility of career maneuvering as it was inner strife. (Go back and watch the episodes “Woods” and “New Jazz.”) That was part of its radiance, too. Even when it dipped into the surreal, which it frequently did with Paper Boi, the show’s exhaustive imagination was always bound to reality. Atlanta was fiction only in genre; the organs of the series—its heart, brain, and lungs—were adapted from the body of life.